Cultural Cocktail Hour

Review: Francis Alÿs’ Fabiola Portraits at LACMA

An overwhelming sea of red greets visitors entering the Francis Alÿs’ Fabiola exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Arts. The darkly colored room on the museum’s second floor houses a hushed shrine.

The LACMA pilgrim entering the room is struck at first glance by the undeniable likeness between more than 300 veiled women, mostly in red, mostly in profile. Upon closer observance, however, the hundreds of Fabiolas play with the viewer, exposing their differences. Some Fabiolas stare ahead somberly. Other lips convey the hint of a smile. One fetching Fabiola resembles a 40’s movie star. Another typifies a Plain Jane. One is etched onto velvet, while another is comprised of beans. The exhibit transports the sacredness of iconography into the profane territory of flea markets, ceramics, and beans.

Francis Alÿs, the collector behind the Fabiola exhibit, amassed at least 300 renditions of Saint Fabiola, the noble Roman saint who became a patron of nurses and abused women.

Alÿs’ acquisition of Fabiolas took him from regions as far-flung as Latin America and the Netherlands where he scoured high and low, from antique shops to open air markets.

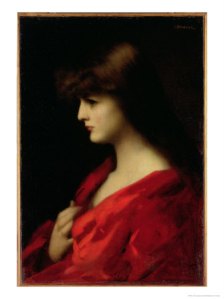

The iconic image that we now have of Fabiola originates from a now lost portrait of Fabiola, painted by the nineteenth century French academic, Jean-Jacques Henner.

A reproduction of the now lost Henner portrait of Fabiola. The color and profile are similar, but the harsh countenance is very distinct from the 20th century Fabiolas currently at LACMA.

But while Henner’s rendition (reproduced here) is stern and austere, the 20th century Fabiolas discovered by Alÿs exhibit a soft youthful countenance befitting the nurturing saint who founded Rome’s first hospice for the poor.

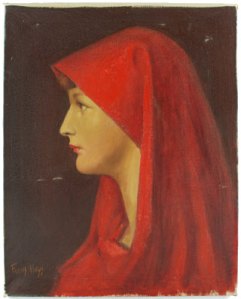

In fact, the sweet faces in the majority of the Fabiola portraits more closely resemble the sitter in another of Henner’s paintings, the Study of a Woman in Red.

The face of this Henner painting, the Study of a Lady in Red, strongly resembles the majority of the faces in the more than 300 Fabiolas at LACMA. Perhaps modern artists conflated the original lost Henner Fabiola portait with this painting.

The proliferation of Fabiolas demonstrates not only the saint’s lasting universal popularity but also begs the age-old question, “What is art?” Can it be found in flea markets? Francis Alÿs had clear stipulations for objects to be included in the exhibit.

Forbidden were printed reproductions. In the age of Xerox copies, the integrity of the Fabiola portraits lies in the fact that they are all constructed by hand, mostly anonymous hands.

One of the many Fabiola Portraits currently at LACMA. The Fabiola Portraits embody the democratization of art. Art, like saints, should not be relegated to closed off reliquaries. They both exist in churches, temples, and flea markets. The word “Profane” originates from the Latin “Outside the Temple.” In the Fabiola Portraits, Francis Alÿs, takes the profane and makes it sacred.