Cultural Cocktail Hour

Cultural Cocktail Hour heads to San Francisco: “Masters of Venice” at the de Young Fine Arts Museum

Masters of Venice: Renaissance Painters of Passion and Power

By Leticia Marie Sanchez

It was the best of times. It was the best of times.

Stepping into San Francisco’s de Young Museum of Fine Arts is stepping into the Venetian Renaissance. Entering the exhibit you feel like one of the many pilgrims shown in the de Young’s reproduction of Bellini’s panoramic scene on Piazza San Marco.

Gentile Bellini: Procession in the Piazza San Marco, 1496.

The Masters of Venice applies to the city’s painters and power-brokers. Canvases of Venetian merchant ships made the city a maritime power. Canvases of avant-garde artists during the Quattrocento and Cinquecento like Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and Tintoretto pushed the creative envelope.

The Venetian School revolutionized painting by shifting away from rigid wood panels, favoring canvases as a medium of choice as well as oil painting instead of the quickly drying and less-forgiving egg-based tempera.

The ability to lavish layer upon layer of oil produced a richness of hue and a glossy dimension that distinguished these artists from their Florentine counterparts for whom Disegno, or design, was paramount. For the Venetians color reigned supreme.

Moretto da Brescia. Portrait of a Young Woman, circa 1540

Not only does the exhibit give the viewer a sense of the Venetian Renaissance, it provides context to the paintings’ permanent home in Vienna. By a stroke of luck and excellent timing, the entire temporary exhibit (Closing February 12th) was transferred lock, stock, and barrel to San Francisco (as the only US destination) from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, which houses the collection of the Hapsburg Empire.

Who is the gentleman surrounded by so many paintings? One of the first galleries in the de Young exhibit contains an intriguing depiction of Hapsburg mega-collector Archduke Wilhelm standing in his well-stocked Brussels gallery. This lucky man eventually owned many of these Venetian beauties.

Look closely at these “paintings within the painting.” Like a game of clue, you will discover nine of the Archduke’s paintings in the de Young, including Giorgone’s The Three Philosophers, Titian’s Christ and the Adulteress, and Titian’s Il Bravo.

This clever image at the exhibit’s opening encourages the viewer to embark on a treasure hunt through the galleries to spot the Archduke’s paintings. What once belonged to the Archduke, now belongs to everyone in the de Young, if only for another month.

Above, David Teniers the Younger. Hapsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his Gallery in Brussels. Circa 1650

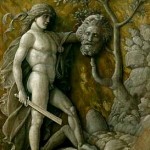

Do not miss Andrea Mantegna‘s “David with the Head of Goliath.”

Mantegna set out to prove that painting was just as good as sculpture, and he certainly proved his point. The sculptural quality of this David sets it apart from every other work in the exhibit.

Andrea Mantegna. ”David with the Head of Goliath. Circa 1490.

“The Fashion Police won’t arrest me”

The Sumptuary Laws of Renaissance Venice governed the manner of dress and required that citizens dress within norms governing each specific class.

The rules permitted extravagant colors for the chosen few, like this red-garbed Procurator of San Marco, the second most powerful man in Venice after the Doge.

Bernardino Licinio. Portrait of Ottavio Grimani. 1541

”Et tu Pentheus?”

Titian’s “Il Bravo” illustrates the moment in Ovid’s Metamorphoses when Bacchus is arrested by Pentheus, King of Thebes.

While at the exhibit, be sure to get close to Pentheus’ armor. Its shiny dimensionality reflects Titian’s superb talent in evoking luminosity.

Tiziano Vecellio, “Titian.” Il Bravo. Circa 1520.

Who is the real voyeur, here?

Tintoretto’s “Susana and the Elders” depicts the Biblical tale of a virtuous woman spied on by two elderly lechers. Despite their futile attempts to seduce and slander, the men are soon proven prevaricators.

The painting embodies the literal and figurative contrast between light and dark. Up close, one can admire Tintoretto’s skillful rendering of the luxurious jewelry, earrings, and the human body. It is a bit ironic that a morality tale about the pitfalls of voyeurism presents us the voyeurs, or viewers, rather, with an unabashed celebration of a voluptuous nude.

Masters of Venice: Renaissance Painters of Passion and Power

By Leticia Marie Sanchez

It was the best of times. It was the best of times.

Stepping into San Francisco’s de Young Museum of Fine Arts is stepping into the Venetian Renaissance. Entering the exhibit you feel like one of the many pilgrims shown in the de Young’s reproduction of Bellini’s panoramic scene on Piazza San Marco.

Gentile Bellini: Procession in the Piazza San Marco, 1496.

The Masters of Venice applies to the city’s painters and power-brokers. Canvases of Venetian merchant ships made the city a maritime power. Canvases of avant-garde artists during the Quattrocento and Cinquecento like Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and Tintoretto pushed the creative envelope.

The Venetian School revolutionized painting by shifting away from rigid wood panels, favoring canvases as a medium of choice as well as oil painting instead of the quickly drying and less-forgiving egg-based tempera. The ability to lavish layer upon layer of oil produced a richness of hue and a glossy dimension that distinguished these artists from their Florentine counterparts for whom Disegno, or design, was paramount. For the Venetians color reigned supreme.

Moretto da Brescia. Portrait of a Young Woman, circa 1540

Not only does the exhibit give the viewer a sense of the Venetian Renaissance, it provides context to the paintings’ permanent home in Vienna. By a stroke of luck and excellent timing, the entire temporary exhibit (Closing February 12th) was transferred lock, stock, and barrel to San Francisco (as the only US destination) from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, which houses the collection of the Hapsburg Empire.

Who is the gentleman surrounded by so many paintings? One of the first galleries in the de Young exhibit contains an intriguing depiction of Hapsburg mega-collector Archduke Wilhelm standing in his well-stocked Brussels gallery. This lucky man eventually owned many of these Venetian beauties.

Look closely at these “paintings within the painting.” Like a game of clue, you will discover nine of the Archduke’s paintings in the de Young, including Giorgone’s The Three Philosophers, Titian’s Christ and the Adulteress, and Titian’s Il Bravo.

This clever image at the exhibit’s opening encourages the viewer to embark on a treasure hunt through the galleries to spot the Archduke’s paintings. What once belonged to the Archduke, now belongs to everyone in the de Young, if only for another month.

Above, David Teniers the Younger. Hapsburg Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his Gallery in Brussels. Circa 1650

Do not miss Andrea Mantegna‘s “David with the Head of Goliath.”

Mantegna set out to prove that painting was just as good as sculpture, and he certainly proved his point. The sculptural quality of this David sets it apart from every other work in the exhibit.

Andrea Mantegna. ”David with the Head of Goliath. Circa 1490.

“The Fashion Police won’t arrest me”

The Sumptuary Laws of Renaissance Venice governed the manner of dress and required that citizens dress within norms governing each specific class. The rules permitted extravagant colors for the chosen few, like this red-garbed Procurator of San Marco, the second most powerful man in Venice after the Doge.

Bernardino Licinio. Portrait of Ottavio Grimani. 1541

”Et tu Pentheus?”

Titian’s “Il Bravo” illustrates the moment in Ovid’s Metamorphoses when Bacchus is arrested by Pentheus, King of Thebes. While at the exhibit, be sure to get close to Pentheus’ armor. Its shiny dimensionality reflects Titian’s superb talent in evoking luminosity.

Tiziano Vecellio, “Titian.” Il Bravo. Circa 1520.

Who is the real voyeur, here?

Tintoretto’s “Susana and the Elders” depicts the Biblical tale of a virtuous woman spied on by two elderly lechers. Despite their futile attempts to seduce and slander, the men are soon proven prevaricators. The painting embodies the literal and figurative contrast between light and dark. Up close, one can admire Tintoretto’s skillful rendering of the luxurious jewelry, earrings, and the human body. It is a bit ironic that a morality tale about the pitfalls of voyeurism presents us the voyeurs, or viewers, rather, with an unabashed celebration of a voluptuous nude.

Jacopo Rusti, called Tintoretto. Susanna and the Elders. Circa 1560

Perhaps Tintoretto’s work reflects the nature of art itself. While contemplating a work of art, whether painting, music, or drama we become privy to a complete stranger’s exterior and sometimes psychological world.

The moment that the artist reveals himself or herself to us, are we also voyeurs?

Masters of Venice: Renaissance Painters of Passion and Power from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

de Young fine arts Museum of San Francisco

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive San Francisco, CA 94118

415.750.3600