Cultural Cocktail Hour

Review: In the Raw: A fresh take on the Renaissance at the Getty Center- A Must See Exhibit

In the Raw: A Fresh take on the Renaissance at the Getty Center

by

Leticia Marie Sanchez

The Renaissance Nude

Oct 30, 2018- Jan 27, 2019

The exhibit on the Renaissance nude at the Getty does not pull any punches- it is authentic, raw, and illuminating. What makes it stand out is that idealization is not the name of the game. Instead, the exhibit gets to the heart of the matter. There are books on anatomy, studies from morgues, saints being tortured, bodies that are emaciated and infirm contrasting with ripe, seductive, athletic, forms. The lushness of a painting like Titian’s Venus Rising From the Sea is viewed within the context of the nude form in all its facets.

Unlike other Renaissance exhibits which focus on iconography alone, the Getty exhibit explores what proves more fascinating, the intriguing world behind the scenes: the courtly intrigue, royal mistresses, preparatory drawings, studies from the morgue, humanistic philosophy, and religious loopholes.

In addition to keeping the theme innovative, the exhibit allows one to see paintings that have never left their home countries and institutions and may never do so again. Getty director Timothy Potts revealed that “this is a major event for the Getty and a major event for art history.” The exhibition was curated by Thomas Kren, with Jill Burke and Stephen J. Campbell and with the assistance of Andrea Herrera and Thomas de Pasquale. Following its presentation at the Getty, the exhibition will travel to the Royal Academy of Art in London

While at the exhibit, do not miss these highlights:

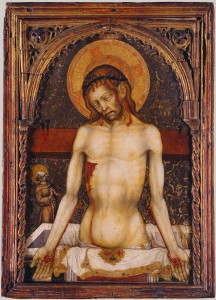

1. Compare and Contrast Giambono’s “Man of Sorrows” with Antonello da Messina’s “Saint Sebastian”

The stylistic evolution of the nude during the Renaissance can be understood when contrasting Giambono’s “Man of Sorrows” (1430) with da Messina’s “Saint Sebastian” (1476-1477). Although only four decades apart, the progression in style is immense. The Man of Sorrows is emaciated, bloody, and realistic, contrasting sharply with the athletic, heroic form of Saint Sebastian who stands in a graceful contrapposto. The later work emphasizes the beauty of the body; even though his body is pierced with arrows, the idealized Saint Sebastian happens not to shed a drop of blood. The image of St. Sebastian pervaded the Renaissance, as it served as a way for artists to showcase their chops.

Man of Sorrows, about 1430

Michele Giambono, Italian, active 1420-1462

Tempera and gold on panel

Painted Surface: 47 X 31.1 cm (18 ½ X 12 ¼ in.)

Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1906

(06.180)

Image: www.metmuseum.org

Ex.2018.1.120

Saint Sebastian,

Antonello de Messina

Saint Sebastian,

Antonello de Messina

Saint Sebastian,

Antonello de Messina

Italian, about 1430-1479

Saint Sebastian, 1476-1477

Oil on Canvas

Unframed: 171 X 86 cm (67 5/16 X 33 7/8 in)

Photo credit: bpk Bildagentur/Gemaeldegalerie Alte Meister/Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut/Art Resource, NY

EX.2018.1.6

2. Titian’s Venus Rising from the Sea is a Showstopper!

The lush texture of Venus‘ hair, coiled in a braid, mesmerizes us as she emerges from the sea. The skin in Titian‘s painting appears soft to the touch; all the elements conspire to seduce the viewer. Venus, the Roman goddess of Love, had become a ubiquitous image by the 1520′s, when major artists throughout Europe, were representing her in different media. The image of Venus also proved to be an intellectual and artistic exercise: artists used this figure to illustrate their mastery of the nude and to compete with the artists of antiquity. For instance, the depiction of “Venus Rising from the Sea” was a competition among Venetian artists. The Getty exhibit also showcases the work of Jan Gossaert, whose very flesh and blood-like Venus appears on a platform, suggesting that she might step off pedestal and join the viewer at any moment.

Venus Rising from the Sea, 1520 Titian (Tiziano Vecellio); Italian, about 1487-1576 Oil on Canvas; Unframed: 75.8 X 57.6 cm (29 13/16 X 22 11/16 in.); Framed: 103 X 84.7 cm (40 9/16 X 33 3/8 in)

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh Accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by HM Government (hybrid arrangement) and allocated to the Scottish National Gallery, with additional funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund; the Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation), and the Scottish Executive. 2003. Ex. 2018.1.88

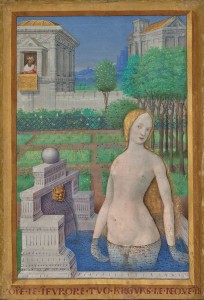

3. Religious Voyeurism and Bathsheba Bathing

In the Bible, King David is a voyeur; he secretly watches the married young woman Bathsheba as she bathes and becomes so besotted with her that he has her husband Uriah sent to the front lines of battle where he is killed.

It is surprising to see such an unabashedly nude image in a prayer book. Thomas Kren explained that at the time, Bathsheba was used as a cautionary figure against wantonness for young women.

But there is a second reason, one that links back to the notion of voyeur. According to Thomas Kren, these prayer books were also collected by wealthy male patrons as objects of prestige. The religious narrative gave them the veneer of propriety for collecting this erotic image. Interestingly enough, Queen Anne eschewed the image of the nude Bathsheba for her Book of Hours, preferring instead the images of several unclothed male saints. Even during courtly life during the Renaissance what was good for the goose was good for the gander.

Leaf from the Hours of Louis XII; Jean Bourdichon (French, 1457 – 1521) Bathsheba Bathing 1498–1499; Tempera and gold on parchment; Leaf: 24.3 × 17 cm (9 9/16 × 6 11/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS 79 recto 2003.105.recto

4. The Flogging of St. Barbara- the nude through a religious lens

This visually arresting piece depicts the torture of Christian martyr Saint Barbara. This work has never before been seen outside of Finland and comprises the bottom portion of a wood and oak panel. What is also significant about this piece is its contextual parallel to the image of Bathsheba in the book of prayers: the depiction of a beautiful topless female was allowed because of the Christian narrative.

Konrad von Vechta; German, about 1380-about 1440 The Flogging of St. Barbara; 1420; Tempera on wood and oak relief; Unframed: 193 X 56cm (76X22 1/16 in.) National Museum of Finland; Photo: The Picture Collections/The Finnish Heritage Agency; EX.2018.1.43.2

5. Jean Fouquet- Another Showstopper- The King’s Mistress as Virgin

In a bold, risqué move, King Charles VII of France, asked that his mistress, Agnès Sorel, famed for her beauty, be depicted as the Virgin Mary. What is even more unusual, is that the Virgin’s bare breast was not used in context of nursing an infant, as the child is not cradled to her breast. Instead, Agnès Sorel’s body is proudly displayed for its beauty alone. Jean Fouquet- or Charles VII- may have been inspired by the legendary tale of the ancient painter Apelles who represented Campasque, the mistress of Alexander the Great, nude. What is different between Fouquet’s painting and that of Appeles is the mistress being depicted as a religious icon. Thomas Kren revealed that Foquet’s painting was one of the only times he could recall a mistress being painted unclothed as the Virgin. Kren, also revealed that this iconoclastic style was so shocking for the era, that it was not repeated or emulated after King Charles VII’s time.

Jean Fouquet

French, born about 1415-1420, died before 1481

Madonna and Child Surrounded by Angels, 1454-1456

Oil on panel

Unframed: 92 X 83.5cm (36 ¼ X 32 7/8 in.)

Courtesy of Koninlijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen.

Image © www.lukasweb.be-Art in Flanders vzw, photo Dominique Provost

EX.2018.1.17