Cultural Cocktail Hour

Review- Hope Springs Eternal: “Manet and Modern Beauty at the Getty Center”

Édouard Manet French, 1832 – 1883 Flowers in a Crystal Vase, about 1882 Oil on canvas Unframed: 32.7 × 24.5 cm (12 7/8 × 9 5/8 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Collection,1970.17.37 Image courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington EX.2019.3.100

Hope Springs Eternal:

Manet and Modern Beauty

at the Getty Center

by

Leticia Marie Sanchez

October 8, 2019 to January 12, 2020

Manet and Modern Beauty at the Getty Centeris a MUST-SEE exhibit, not only due to the abundant works on view and the insight into the later style of groundbreaking artist Édouard Manet, but also due to the overwhelmingly inspiring perspective into the life of an artist who never gave up hope, painting some of his most exquisite works during his final days.

Curated by Getty curators Scott Allen and Emily Beeny and Gloria Groom, chair of European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago, this is the first major museum exhibition to focus on Manet’s late work. Co-organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, the large-scale exhibition features more than ninety paintings and drawings.

According to Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, “Manet is a titan of modern art, but most art historical narratives about his achievement focus on his early and mid-career work, Many of his later paintings are of extraordinary beauty, executed at the height of his artistic prowess- despite the fact that he was already afflicted with the illness that would lead to his early death.”

Here are some highlights to give you new insights into this seminal artist:

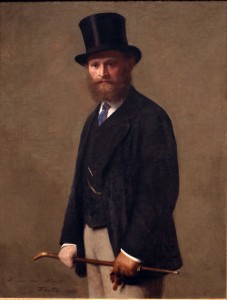

- Manet as Dandy: Henri Fantin-Latour’s portrait of Édouard Manet

Although Manet has been hailed by many as the Father of Modernism and his earlier avant-garde works including Olympia and Le Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe sent shockwaves through the French art establishment, this portrait is a reminder that Manet did not view himself as a marginalized iconoclast. This depiction of him as a dandy and social creature illustrates the fact that Manet wanted to be accepted by prominent society and, in fact, craved the approval of the French Salon, which had rejected him for so many years. Fantin-Latour’s portrait depicts Manet as an sophisticated figure of fashion. In fact, Manet never exhibited his works with the rebellious Impressionists. The eventual acceptance of his artistic merits by the Salon in his later years was a personal coup for him.

Henri Fantin-Latour French, 1836 – 1904 Portrait of Édouard Manet, 1867 Oil on canvas Unframed: 117.5 × 90 cm (46 1/4 × 35 7/16 in.) The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund, 1905.207 EX.2019.3.58

2. Portrait of Antonin Proust

Antonin Proust was a politically influential figure who helped Manet to garner acceptance by the art establishment of his time. He and Manet met in art school and became friends. Proust, however, took a different career path, becoming a politician and eventually holding the position of Minister of Fine Arts. Because of Proust’s advocacy, Manet was made a member of the prestigious Legion of Honor in 1881. Proust also wrote Manet’s memoirs so it is only fitting that Manet painted this portrait of one of his artistic champions.

Édouard Manet 2. French, 1832 – 1883 Portrait of Antonin Proust, 1880

Oil on canvas Unframed: 129.5 × 95.9 cm (51 × 37 3/4 in.) Toledo Museum of Art, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 1925.108 Photo: Richard Goodbody Inc., New York EX.2019.3.98

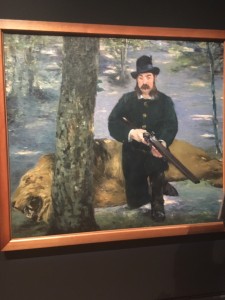

3. Mr. Eugène Pertuiset, the Lion Hunter

This painting is a Must-See for humorous purposes. Manet had been denied a medal by the Salon for so many years. It was completely ironic that it was this shocking, somewhat unpalatable image that first garnered him the respect which had eluded him for so many years.

Édouard Manet, French, 1832 – 1883 Mr. Eugène Pertuiset, the Lion Hunter, 1881 Oil on canvas Unframed: 150.5 × 171.5 cm (59 1/4 × 67 1/2 in.) Collection Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, Gift Gastão Vidigal and Geremia Lunardelli, 1950 MASP.00079 Photo: João Musa EX.2019.3.6

4. Woman Reading

This beautiful work is a highlight of the exhibit for many reasons. Firstly, upon close observation, can see can see what curator Emily Beeny aptly described as the “peripatetic brushstrokes.” But secondly, this work appears, on first glance, to take place at an outdoor café; yet, the inexplicable winter coat in the summery outdoor garden setting is the first clue that there is artifice involved and that this scene was actually staged in Manet’s studio. Why? In his later years, Manet had difficult walking and eventually had his leg amputated, which led to his demise. This painting underscores his tenacity to continue his art, despite significant physical challenges. Édouard Manet French, 1832 – 1883 Woman Reading, about 1880-1881 Oil on canvas Unframed: 61.2 × 50.7 cm (24 1/8 × 19 15/16 in.) The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection, 1933.435 EX.2019.3.55

5. Jeanne (Spring) and Autumn

These two companion works are a cornerstones of the exhibit. According to Scott Allan, Associate Curator of Paintings at the Getty Museum, “Jeanne was an unalloyed critical success for Manet, making it a rare exception in a career dogged by scandal, controversy, and disappointment.” This image of youthful springtime, which appears effortless was actually worked on painstakingly by Manet. The female subject has the perfect upturned nose that was idealized in fashionable French society at the time. Step closer to the painting at the exhibit, and you will see a patch of pale green in the background of the subject’s profile. This green patch illustrates that Manet meticulously worked and re-worked her profile until it attained the level of perfection that he desired.

Jeanne and Autumn ( the latter of which hails from Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy ) have not been viewed together in forty years. The subject of Autumn, Méry Laurent, was a fashion maven of her era and her robe was furnished by Proust himself. Unfortunately, Manet passed away before he was able to complete all four of the seasons.

Édouard Manet French, 1832 – 1883 Jeanne (Spring), 1881 Oil on canvas Unframed: 74X 51.5 cm (29 1/8 x 20 1/4 in) Framed: (8.7 X 75.9 X 9.2 cm (38 7/8 X 29 7/8 X 3 5/8 in). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Accession No. 2014.62

Édouard Manet French, 1832 – 1883 Autumn (Méry Laurent), 1881 or 1882. Oil on canvas Unframed: 72 × 51.5 cm (28 3/8 × 20 1/4 in.). Musée des beaux-arts, Nancy Photo: P. Mignot EX.2019.3.18

6. Hope Springs Eternal: Bouquets painted in Manet’s last days

These effulgent bouquets were painted in the last year of Manet’s life and evince his tenacity to paint exuberant beauty despite physical suffering. According to Emily Beeny, associate curator of drawings at the Getty Museum, these flowers were “the last fireworks of his dying days”

Édouard Manet French, 1832 – 1883

Moss Roses in a Vase, about 1882

Oil on canvas Unframed: 55.9 × 34.6 cm (22 × 13 5/8 in.) Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA EX.2019.3.102

Walking through the exhibit, I was struck by Manet’s determination in the face of intense medical challenges. When he could no longer physically walk to the café, he brought the café to his studio, staging lively works there. When he was dying, he painted the most breathtaking florals of his career. Even more than his formidable talent, I was inspired by Manet’s spirit of resilience. We are all the better for it and fortunate to gaze upon works by an artist who never gave up.